It’s been a 100 years since the guns went silent.

A century since we bombarded the other side with mustard and chlorine gas.

It was to have been The Great War – the war which ended war.

My grandfather was at Passchendaele. It’s also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, and it went from July to November of 1917. Both sides each lost between 200,000 and 420,000 men. It was hard to tell as so many were lost in the mud, explosions and general gore. My grandfather didn’t really like to talk about that time, but he did show us his “war wounds” – the scarred feet from his bout of Trench Foot.

I never really appreciated it all until I visited the site and war graves in 2001. Then I understood his far away look and deep sadness each November. My father, a WWII veteran, would join him at sunset each November 11 and drink a silent glass of whiskey. It was their salute to their fallen, but never forgotten comrades.

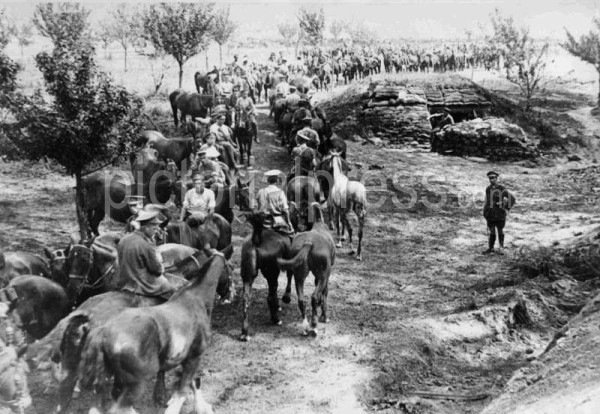

The years rolled by and I never forgot what my grandfather told me. His happier reflections centred around the fact that he had been able to ride with General Pershing. He would talk about how important this man was and how important the bay mare my grandfather rode was. Again, it is only now that I reflect also upon that unknown horse, who I think one of my aunts may have been named after.

Each year the Royal British Legion sells their red poppies. The poppy is a sign that we haven’t forgotten and it helps raise necessary funds for today’s soldiers. The red poppy is currently everywhere. But what about the purple poppy? The purple poppy is hard to find. It is the flower that reminds us of how many animals were lost in The Great War.

Sixteen million, that’s right million, animals were used during World War I. Horses, dogs, cats and birds filled the trenches of both sides. Dogs provided companionship but were also used to help find the wounded, carry first aid when it was not possible for a human to do so as well as to sniff out bombs. They were also instrumental in finding the dead. As you probably know, birds, specifically carrier pigeons, were used to send messages. Anyone caught with a carrier pigeon was immediately branded a spy and both bird and human were summarily executed. Cats were the first suicide bombers as they would stealthily meander across no man’s land to opposing army’s trench in search of food. Their effectiveness is still open debate. Then there were the equines.

Eight million horses and countless mules and donkeys died in the Great War. Britain provided over a million horses in the European Campaign and another 65,000 in the Mesopotamia Campaign . The USA sent 1 million over via ship and another 185,000 with their army. The British “topped up” their animal forces at about 100,000 horses each year. The French provided 17 regiments of mounted soldiers. The German, Austrian, and Russian forces had equal numbers. The various allies of Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Italians, Turks and Slavs all provided immense numbers of equines. These animals were used to transport ammunition and supplies to the front, pull ambulance wagons, as well as participate in numerous failed cavalry charges.

Eight million horses and countless mules and donkeys died in the Great War. Britain provided over a million horses in the European Campaign and another 65,000 in the Mesopotamia Campaign . The USA sent 1 million over via ship and another 185,000 with their army. The British “topped up” their animal forces at about 100,000 horses each year. The French provided 17 regiments of mounted soldiers. The German, Austrian, and Russian forces had equal numbers. The various allies of Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Italians, Turks and Slavs all provided immense numbers of equines. These animals were used to transport ammunition and supplies to the front, pull ambulance wagons, as well as participate in numerous failed cavalry charges.

For the British, they lost 1 horse for every 2 men.

These animals not only died due to warfare injuries, they died from shellfire, appalling weather, overwork and starvation. Some troops even went as far as to kill the horses for food for themselves.

You may have seen the stage play or film, War Horse. Joey’s story is rather accurate. We all held our breath as tears rolled down our faces when the injured, blind Albert Narracott wanders in desperation to save Joey, his horse, from being shot by the unit Commander. At the end of the war many horses, mules and donkeys were simply abandoned. They were also sold for slaughter to feed the starving human population. Many were simply shot so that the local population would have no access to them. As the troops came home, often their most trusted companion did not. Britain tried to repatriate as many as they could and it was about half a million, but of the nearly 600,000 Australian horses only 1, Sandy, returned home.

Blue Cross Animal Charity began in 1887 as Our Dumb Friends League, but changed its name in 1912 after the Balkan Wars. Its purpose was to help the horses of war. It was instrumental during World War I in making sure that horses had proper treatment for the host of diseases that were rife – ringworm, tapeworm, mange, equine influenza and anthrax were common. They also helped oversee surgery for hoses caught in gun fire. Blue Cross is still active today supporting horses who have been abandoned, neglected or wilfully injured. They rehabilitate them and try to safely re-home as many as possible.

Blue Cross Animal Charity began in 1887 as Our Dumb Friends League, but changed its name in 1912 after the Balkan Wars. Its purpose was to help the horses of war. It was instrumental during World War I in making sure that horses had proper treatment for the host of diseases that were rife – ringworm, tapeworm, mange, equine influenza and anthrax were common. They also helped oversee surgery for hoses caught in gun fire. Blue Cross is still active today supporting horses who have been abandoned, neglected or wilfully injured. They rehabilitate them and try to safely re-home as many as possible.

After the war, the millions of donkeys left in the Middle East were  cruelly treated. A group of British women were appalled by what they saw and did what they could to provide appropriate veterinary care and food for these animal heroes. In 1930 they formally created The Brooke Trust which operates to this day as a charity to help the donkey population in the Middle East and around the world.

cruelly treated. A group of British women were appalled by what they saw and did what they could to provide appropriate veterinary care and food for these animal heroes. In 1930 they formally created The Brooke Trust which operates to this day as a charity to help the donkey population in the Middle East and around the world.

There is a good reason to wear a purple poppy. These animals didn’t ask to go to war nor did they celebrate it. They died for us. They gave their all and until recently no one spoke on their behalf. On 11 November I shall remember those who fell, both human and animal, and I shall remember my grandfather and his bay mare which he left behind in France.

Next year, please wear a purple poppy along with red poppy to Remember All Who Gave Their All.